Dear Ismail,

hope you are well.

I am sending you my brend new article "Cartoons: the art of dissenters".

This article is about the ways of development of modern cartoon art.

I am very interested in your opinion.

Sorry for troubling you.

Best wishes,

Vladimir |

|

Cartoons:

the Art of Dissenters

|

|

| by

Vladimir Kazanevsky

|

| This article attempts to demonstrate the

new trends of modern cartoons "without captions". To do

this, we must consider the stages of emergence, formation and

development of this genre of art up to the present day. Has the

imaginative world of cartoons changed? Did the emergence of personal

computers and the Internet influence the visual embodiment of

cartoons? Have the "spirit of the absurd" and

philosophical foundations of cartoons changed? And finally,

what is the place of cartoon art in today's society? |

|

Modern

cartoons "without captions" have existed for almost a

century. These cartoons appeared in the 1930s in France and the

United States under the influence of innovative ideas in the visual

arts, literature, theater and philosophy.

Cartoons "without captions" are fundamentally

different from the traditional centuries-old comic and from

satirical graphics, which still exist today, for example in the form

of political cartoons. This essay deals exclusively with the cartoon

"without captions", leaving aside other forms of cartoon

art, which were developed under different laws. In this essay, we

will refer to the cartoon "without captions" simply as

cartoon.

|

| First

of all we are interested in whether the art of cartoons has changed

during its existence. Are "grotesque, ironic, buffoonery"

and a "humor of paradoxes, oddities and quirks" still the

characteristics of cartoons in the present day? These properties

were given to cartoons by researcher Nina Dmitrieva at the time of

their emergence in the 1930s [1, 256]. |

| Not

only the visual representations, but also the semantic contents of

cartoons has

changed almost imperceptibly in recent decades. This is primarily

caused by a variety of radical social phenomena, as well as the

emergence of new technical possibilities and means of communication. |

| Of

course, the core of a cartoon is the semantic content. It is here

that we find the "comic charge", the philosophical and

other conscious or subconscious ideas of the author, or the lack of

them. What happened to "humor of paradoxes, oddities and quirks"? |

| The

lonely man on a small island decorated by a symbolic palm tree is

almost gone from cartoons. There were simply too many such men, a

whole army, and they did not seem quite so lonely anymore. They

filled the magazines, newspapers and the digital space of the

Internet. Viewers no longer believed in the lonely men on their

desolate islands. However, this did not end the notion of

existential loneliness as a subject for cartoons. Other, modern,

symbols have come in place of the islets, which we will discuss

later. |

| The

blow by a bat or stick on the head of someone coming around a corner

has ceased to be unexpected. The artists understand this and do not

hide their insidious characters around corners anymore. Instead,

they began to look for other ways to "blow" the viewer.

Roughly the same thing happened with the act of slipping on a banana

peel. Heroes of cartoons began to get around this obstacle invented

by artists. Another cartoon cliche which has become outdated is the

"cake in the face". However, even now there are some cases

where the cartoon hero suddenly throws a cake in the face of someone.

It looks like the work of an artist without inspiration. Instead of

coming up with a new idea, the artists decided to throw a stale cake

to the viewer. Is this not "strange humor, full of the

grotesque and of oddities"? |

| The

leaning tower of Pisa will fall down only when cartoonists are tired

of drawing this image. |

| The

eternal creative "helpers" of cartoonists, the characters

of Don Quixote and Sancho Pаnzа, have become less likely

to feature in the graphic works of satirical artists. Maybe finally

cartoonists became

ashamed for using Miguel de Cervantes' famous characters in vain? |

| In

cartoons, the ostrich continues to bury his head in the sand. But he

does this ever more infrequently

and reluctantly. Are cartoonists aware that in real life,

ostriches never do this? When these birds are scared of something

they just run away. And so another cartoon myth gradually disappears. |

| The

most persistent fighter for peace is still the white dove. This

image was drawn by Pablo Picasso for the First World Peace Congress

in 1949. Almost immediately after the appearance of white bird as

the emblem of peace, it playfully migrated to cartoons. So far, the

dove with an olive branch in its beak is the most loyal supporter of

pacifism, a fighter against militarists of all stripes. |

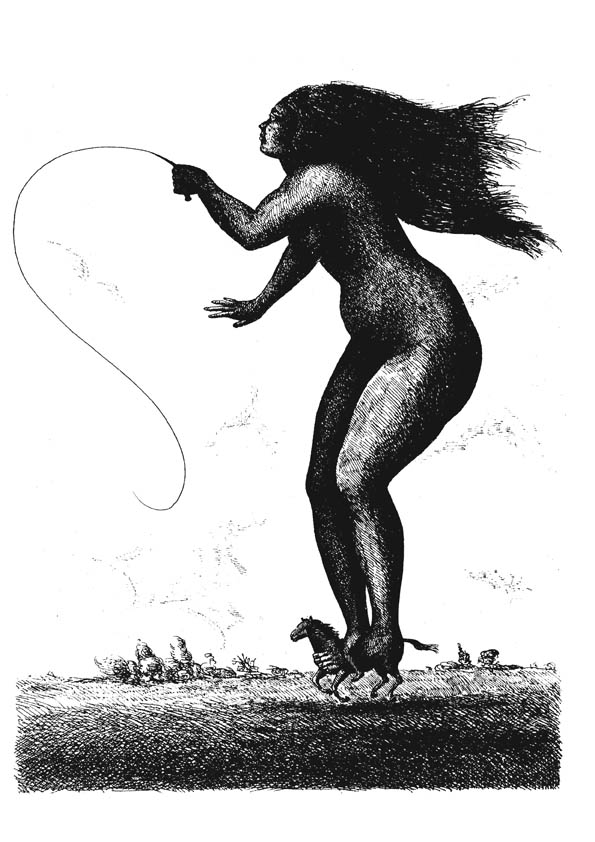

| In

antiquity, Death was already portrayed as a gaunt old woman in a

black cloak and with a scythe. The old women which

is depicted in the ancient frescoes, in the engravings by

Albrech Dürer and in other works is strikingly similar. There is a

feeling that artists have always drawn the same mysterious lady.

Death did not escape the attention of cartoonists. For them there is

no detail of life, even the most tragic, that would not be subject

to reflection and witty ridicule. They believe that, as Arthur

Schopenhauer said, "death does not interrupt the eternal

becoming, it kills only the individual." Illustrations of this

philosophic statement can serve numerous cartoons, which show the

coitus of a mortal man with old bony woman. And the apotheosis of

"eternal becoming" are cartoon images of pregnant Death (Fig.1). |

|

|

| There

are a lot of cartoons that are somehow connected with death. They

depict executions, suicides, war, murder, and so on. Basically,

these cartoons are in the area of black humor, the main purpose of

which, according to Freud, is "to avoid dissatisfaction from

internal sources" [2]. By resorting to black humor, cartoonists

try to overcome the great tragic irony that is life. As noted by

Boris Tsigulevsky, the artist's position in this case is "not a

mockery and pretense (this

is on the side of life) and not a game or humor, but his serious

concern about their fate, effort, or even heroism" [3]. The

Boston World Dictionary of Literary Terms defines black humor as

"humor meant to overturn moral values, causing a grim

smile." It also says that black humor is a cynical way to

respond to evil and the absurdity of life. According to supporters

of black humor, it "has a psychotherapeutic effect". Black

humor is a way to laugh where every other way of describing the

evil will just evoke crying" [4]. Black humor confidently

settled in the cartoon world. |

| Grim

Sisyphus continues to roll his eternal stone to the top of the

mountain, a Trojan horse can always be found near the gate, Rodin's

thinker continues to pose for artists intent on mocking him. A lot

of funny, sad, proud and evil characters of literature, film,

animation, painting, sculpture and theaters have settled in cartoons.

Alas, many of these "comfortable" images for cartoonists

have become stereotypes, and some of them irrevocably obsolete. |

| Use

of the same images, use of common methods to achieve comic effects,

in the end, led to cartoonists involuntarily repeating predecessors.

The "heuristicity" of cartoons began to fade. Plenty of

cartoon clones began to appear regularly on the pages of newspapers

and magazines at the end of the twentieth century. It was not a

problem of direct plagiarism or imitation, but

a problem of cartoonists thinking in stereotypes. |

| The

cartoon myths" of the past began to gradually dissipate.

Naturally, their place was occupied by something new. |

| Skyjackings

by armed terrorists became frequent at the end of the last

millennium. Subsequently, the press was filled with cartoons in

which the main characters were hijackers. The terrorists in cartoons

hijacked everything in the air, on the ground or in the water. |

| Airplanes

hijacked by terrorists crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City

in the beginning of this century. And then a cartoon appeared which

depicts two planes crashing into giant sizes pencils... |

| The

wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, the "color revolutions"

in Africa, Asia, Europe and numerous of terrorist attacks have

created new characters in cartoons, for example armed men in

camouflage uniforms. One of the most important characters in modern

cartoons became the armed terrorist hiding his face under an evil

black mask. The forces of peace, embodied either by children or

by the dove of peace are fighting against this terrible

character in cartoons. And they win often. But more often they are

defeated. Black humor reigns in cartoons. A terrorist cuts an

unfortunate pencil with a knife like a victim's throat (Fig.2). This

is a new myth in the world of cartooning. |

|

|

| Refugees

fleeing from the terrorist evil have also become new favorite

characters of cartoonists. cartoonists are sympathetic to the

refugees, condemning those who prevent them in their struggle to

find a new life. |

| Supermarket

trolleys confidently settled in the minds of cartoonists. This image

has become a compelling symbol of the consumer society. |

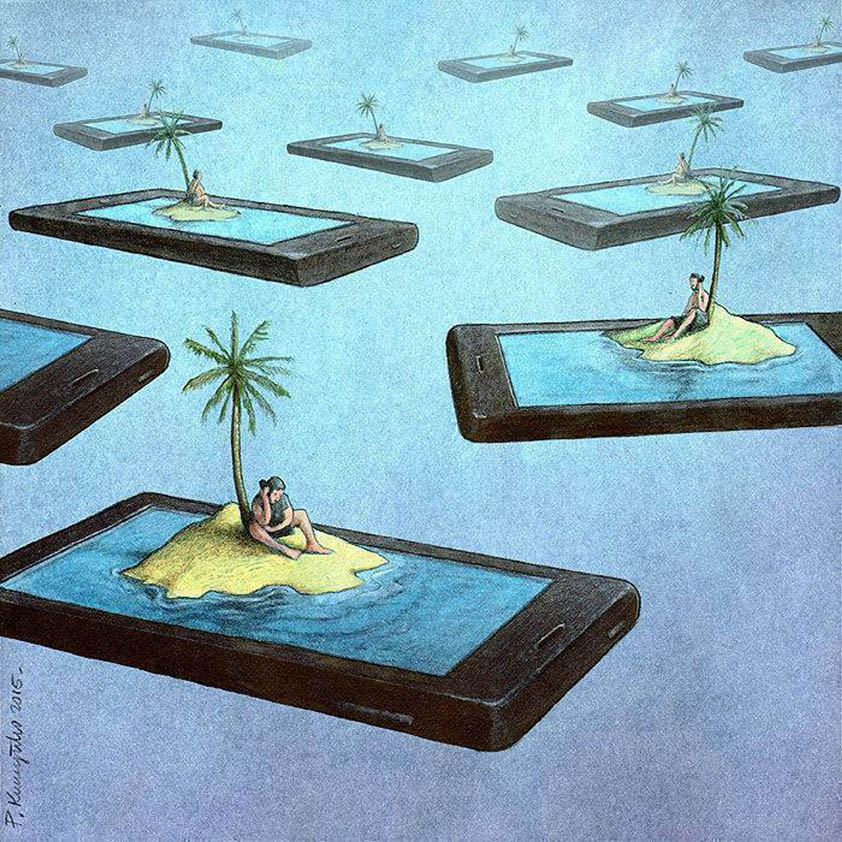

| Cartoonists

have also turned their critical gaze to the Internet. Cartoon

computers and the symbols associated with the Internet have not only

filled the Internet, but also the pages of still existing print

media. Modern cartoonists became friends with the symbol of the

social network Facebook in the form of the letter F. This popular

means of communication once again forced artists to recall the

existential loneliness of man in the world. On the one hand,

formally being a sign of communication between people, this symbol

only emphasizes the loneliness of a real personality. Facebook and

other similar means of communication deny direct human interaction.

Existential anguish that came from the cartoons which depicted a

lonely little man on a desert island, are embodied in the modern

symbol now. A tiny island, a man sitting on the sand, burying his

gaze to the screen of a laptop, tablet or smart phone. And a huge

symbol of social network F, which is vaguely reminiscent of a palm

tree rises above them (Fig.3). |

|

|

| Contemporary

cartoonists draw their inspiration from brand new subjects, images

and symbols. However, this refers only to the myths on which the

semantic content of cartoons is built. Has the "spirit" of

semantic content of cartoons changed? Can we still characterize

cartoons as "humor of paradoxes, oddities and quirks"?

This will be discussed later after we contemplate what happened to

the visual embodiment of the cartoons or, speaking with the words of

Sigmund Freud, with their "façade formations." |

| Cartoons

mostly came in the form of graphic drawings in the first half of the

last century . Cartoons had an inherently

"linear" style; "naive" and "simplistic",

styled to look like children's drawings. The thin vibrating line,

easily showing space and form, suddenly nervously formed a dark mass,

or broke off, leaving a place for "air". Alternatively,

the line can was strong, tearing out shapes from flat space by short

rapid movements of the pen... Thus was the art of cartoonists who

can be considered the pioneers of cartoons. Nina Dmitrieva mentions

cartoonists George Fischer, Saul Steinberg, James Thurber, Maurice

Sinet, Albert Dubou, Jean Effel, Jean-Jacques Sempé, Andre Francois,

Jean-Maurice Bosc, Chaval and Sam Gross. Drawings of these artists

have published in the magazine The

New Yorker. Many researchers, such as Jacques Lefev, believe

that the modern cartoon

originated here and was developed by the creative team of this

magazine [1, 256]. |

| The

first twenty-five years of The New Yorker's existence has been

called a "golden age". The method of selection of cartoons

for publication in the magazine was complicated. Art editors of the

magazine made a preliminary selection of cartoons. Then the

Editorial Board selected the best.

Editor-in-chief Harold Ross, who had unquestionable authority,

made the final decision [5]. Mr.

Ross constantly asked artists to make captions under the cartoons

shorter and shorter, until there appeared cartoons "without

captions". Harold Ross said jokingly, "Everybody talks of The

New Yorkers art - that is, its illustrations - and it has

been described as the best magazine in the world for someone who

cannot read" [5]. |

| A

"corporate" style of comic art of The New Yorker magazine

gradually formed. William Hewison

somewhat tendentiously wrote: "The team of Ross tore up

the old formula of cartoons into pieces and threw a lot of them in

the trash, because those were hard, naturalistic, overloaded. They

strove for simplicity, focus and movement.

Essentially, they gave preference to light and visual humor.

It can be assumed that each of the cartoons, which is created today

in the UK, Europe or anywhere else, is a direct inheritance of

graphic humor of the magazine The

New Yorker of this period " [6]. |

| The

cartoons first appeared to the public in Europe in the comic

magazine l'Os à Moëlle,

which had the subtitle "The official organ of daffy people"

in 1938 [1, 255]. |

| The

"Linear" style has dominated in the world of cartoons

until a few decades ago. |

| Here

we can recall the works of Jean-Jacques Sempe, Jeans Maurice Bosc,

Jacques-Armand Cardon, Maurice

Sinet , Henry Buttner, Claud Serre, Ronald Topor ...( Fig.4). |

|

|

| "Some

people don`t like when I show what`s in their mind,"

said Ronald Topor, who preached a philosophy of "escape

from boredom" [7, 33]. This master of cartoon art said, "A

society is driven by fear. I have fear too, but I am trying to get

rid of unnecessary fears " [7, 37]. Editor of The World

Encyclopedia of Cartoons, Maurice Horn, said that "R. Topor is

a master of black humor who blends the most far-out and disturbing

images into a deceptively classical style" [7, 33]. This

statement is useful to us when we will talk about the

semantic content of the cartoons. |

| Black

and white cartoons continued to dominate after the Second World War.

However, cartoonists also used "color" in their work.

Often, they did this on purpose, because sometimes "color"

is the essence of humor in cartoons. Color can be a kind of

communication in cartoon art. For example, one of the main "color"

characters in cartoons is a chameleon. The coloring of the skin of

this lizard is changed by the color of the environment. Another

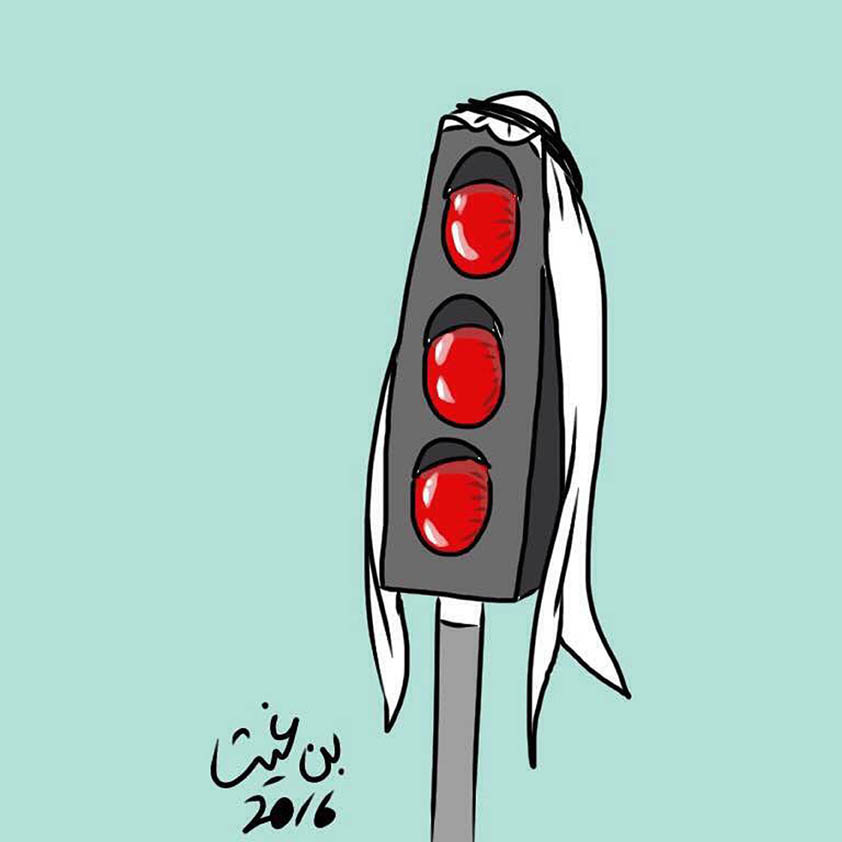

frequenter of cartoons is a street light. For example, cartoonist

can designate the "existential ban without a shadow of hope"

by the red color on street light (Fig.5). In addition, the red color

symbolizes the vitality, passion, energy, enterprise and sexuality.

And as you know, sexuality is tempting for creation of cartoonist.

All that is "below the belt" is amusing, funny and

entertaining to spectators. |

|

|

| How

can I draw a black and white rainbow? Or the artist's palette on

which the paints are mixed? There are cartoons, in which "color"

becomes absolute semantic content, a landmark instrument that

represents a violation of the expected stereotypes of color

relations. Cartoons

which are the based on well-known paintings, such as The

Festival of Fools and The

Tower of Babel by Pieter Brueghel, The

Scream by Edvard Munch, Leonardo

da Vinci`s Mona Lisa etc.

will be not spectacular without colors for viewers. |

| Color

is used in cartoons as an auxiliary element. For example, to attract

the attention of the viewer to the main component of the cartoon, on

which a comic effect is based. In this case, artists use basically

complimentary color combinations, or just one additional color.

Sometimes the color is introduced to create

an emotional and psychological effect in the cartoon. |

| Of

course, at the time when in cartoons the "line" dimnated,

there were artists who preferred "colored" drawings and

paintings. Among these artists were Rene Magritte, Jean-Jacques

Folon, Vlasta Zabransky, Ronald Searle, Miroslav Bartak, Guillermo

Mordillo and others. But the "scenic color" cartoons at

this time was rather rare. |

| By

the end of the last millennium "color" gradually began to

prevail in cartoon art. Cartoon paintings have become increasingly

more common, and now share space with "linear" cartoons in

the pages of magazines and newspapers, international exhibitions and

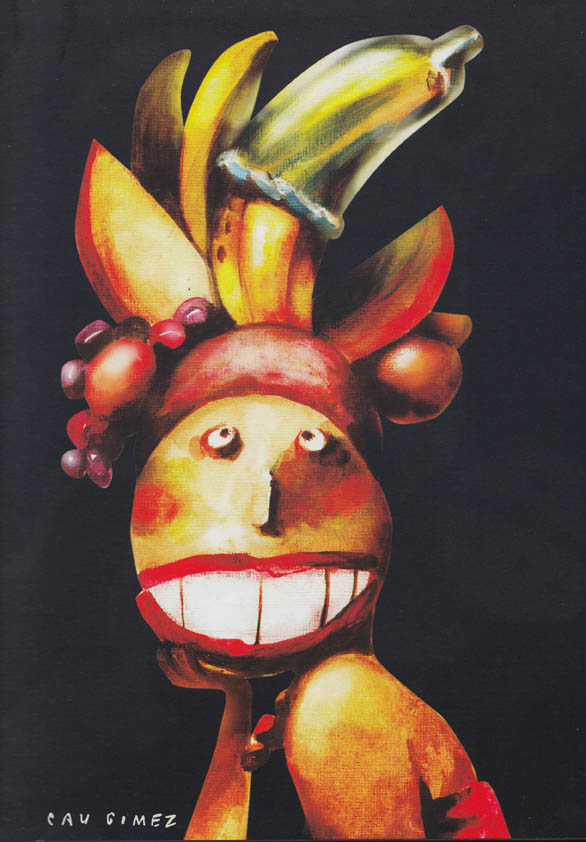

on the Internet. There are brilliant cartoonists-painters, such as

Alessandro Gatto, Jerzy Gluszek, Pawel Kuczynski, Grzegorz Szumowski,

Konstantin Sunnerberg, Muhittin Koroglu, Gerhard

Gepp, Peter Nieuwendijk, Florian Doru Crihana, Dahuan Xia,

Mahmoudi Houmayoun, Cau Gomez... ( Fig.6). |

|

|

| There

are a few reasons why "colors" began to dominate in

cartoons. One such reason is the emergence in the late twentieth

century the personal computers and the Internet. A magician appeared

for the cartoonists named Photoshop. The artists no longer only used

traditional paint but also successfully began to employ virtual

painting techniques. The possibility has appeared to spread the

cartoons free on the Internet with no visible restrictions, without

censorship. A "colored" cartoons look much more attractive

to viewers. After heated debate, the international cartoon community

agreed to give the same status to cartoons that have been created

with the computer as to hand-drawn artwork. Computer-created

cartoons began to

coexist with original works at various exhibitions. Some cartoonists

have become literally virtuosos of computer cartoon art, such as the

Colombian artists Elena Ospina. |

| In

addition, the Internet gave artistseasy access to photographs of

objects and subjects of the world. This helped to saturate the

cartoons of detailing by using the technique of "photographic

accuracy." "Façade formations" of cartoons becoming

more approximate to the real world. Artists such as Pawel Kuczynski,

Agim Sulaj, Paolo Dalponte and others began to create a more

compelling reality of the cartoon world (Fig.7). |

|

|

| In

the last decades there has been a tendency of saturation in cartoons

by "colors", as well as a barely perceptible drift from

graphics to paintings. In addition, the cartoons have moved closer

to realism. In this context, we can talk also about the

metamorphoses of the semantic contents of the cartoons. We will not

talking about the plots of cartoons, new cartoon characters, myths

of the cartoons, which we have already discussed. More interesting

for us is the essence of cartoons. |

| The

process of creating cartoons is subject to certain laws. In his

discussion about the "comic" effects

Arthur Koestler wrote: "Unexpected lateral ideas or

events with two normally incompatible matrices produces a comic

effect..." [8]. This model of "comic" effects is

easily applicable in the art of cartoon.

For example, in the article "Why is it so funny?:

conceptual integration in humorous examples" Seana Coulson made

the attempt to analyze the cartoons, in particular political

cartoons [9]. He used the theory of "conceptual integration"

of Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner, as well as the ideas of

Douglas Hofstadter and Liane Gabora about mixing frameworks of

abstract structures [10,11]. Very interesting for us is "An

Affordance Theory Analysis of Cartoon Humor" by Dean H. Owen

[12] and "A two-stage model for the appreciation of jokes and

cartoons" by Jerry M. Suls [13]. Recall also the sentence by

Maurice Horn: "R. Topor is a master of black humor who blends

the most far-out and disturbing images into a deceptively classical

style". So, we see that creative methods of cartoons are quite

universal. It is by such methods were created cartoons, which we can

define as"grotesque, ironic, buffoonery". |

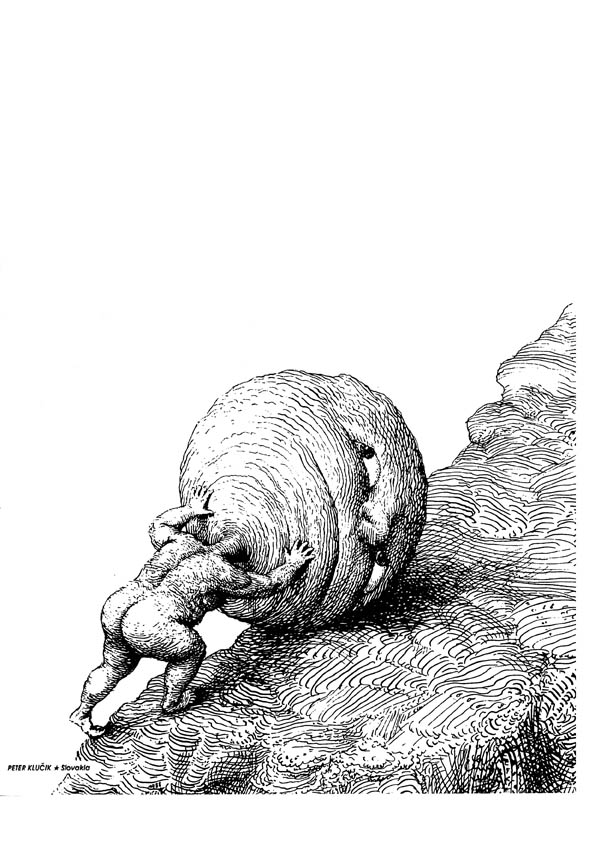

| Albert

Camus believed that the absurd is born from the comparison of not

comparable, alternative, antinomic or conflicting concepts, and

"the wider the gap between the members of the comparisons, the

higher the degree of absurdity" [14, 37]. Thus arose the absurd

world of cartoons which deny common sense. The absurd cartoons, as

well as humor in general, appears when mixing two different concepts.

These are the roots of the "humor

of paradoxes, oddities and quirks." That is, a cartoons is a

reflection of the philosophy

of the absurd. No wonder the brightest hero of many cartoons became

Sisyphus, pushing

his eternal stone to the top of the mountain. The foot of the

mountain, a huge rock, a solitary figure Sisyphus and the top of the

mountain create many opportunities for graphic jokes. However,

foremost cartoonists are interested in the tragic fate of the hero,

his despair and self-affirmation. Such absurdity is desirable for

critical minds. Here is what wrote Albert Camus in his treatise,

"His gaunt face barely distinguishable from the stone. I

see this man coming down heavy, but at a steady pace to the torment

that has no end. At this time, consciousness returned to him

with the breath, inevitable as his suffering. And in every moment,

as he descends from the top down into the lair of the gods, it is

above its destiny. He`s more solid than his stone "[15].

Sisyphus is the hero of absurd (Fig.8). |

|

|

| Recall

also the social absurd phenomenon of depersonalizing people. Arthur

Schopenhauer believed that human history is presented as a world

where "there always is the same person with the same intentions

and the same destiny" [16]. In such a world "each other

becomes like the other..." as noted by Martin Heidegger [17].

The personification of society is a "crowd" and its

representative is "small, miserable, gray man in the crowd who

lost the spirit, seeking for equality," by Friedrich Nietzsche

[18]. Gustave Le Bon in his work "The Psychology of the masses"

characterized the crowd as follows: "Strange in the psychology

of masses is following: ... only by one fact of the transformation

into the mass they acquire a collective soul" [19]. In addition,

Le Bon noted a decline of intellectual achievements of a man by his

dissolving in mass. William McDougall said, that "a slight

intelligences decrease a higher intelligences to their level..."

[20]. Wilfred Trotter in the tendency to unite people towards the

mass in general has seen "a continuation of biological

multicellular all higher organisms" [21]. Around the same time,

in the first half of the twentieth century, the individual leveling

process of persons is reflected in the different genres of art,

including the cartoons. |

|

Characters

of traditional cartoons of the past always had pronounced individual

traits. Artists of the past reflected

the grotesque images of the "carnival world". In the

1930s, cartoonists began to treat their heroes quite differently.

Increasingly, they began to resort to stylization of images using

methods of "naive art". Heroes of cartoons turned into

primitive little men in the crowd, the symbols of the absurd world,

portrayed as herd animals, duplicates traveling from one

cartoon to the next. They came not from the real world but slipped

out of the absurd subconscious of artists. These heroes like to

exist in the impersonal world. |

|

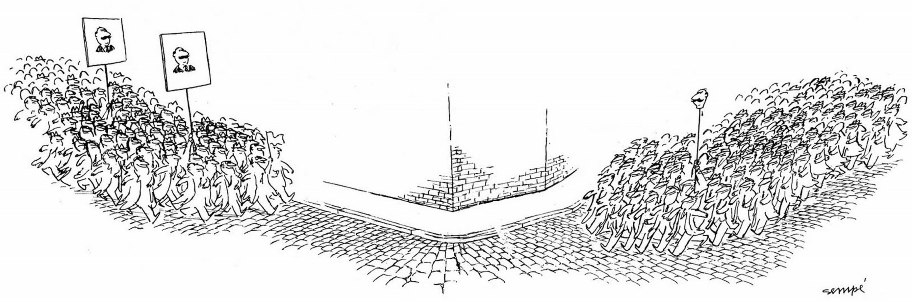

The

depersonalization of man in cartoons is especially convincing where

the crowd is present. Cartoonists mostly have represented the

accumulation of people as the mass of men with "downmix"

intelligence. Artists depicted "the faces of psychological

masses" having "collective

souls" to reflect the masks of "higher multi-cellular

organisms," as absurd monstrosities (Fig.9). |

|

|

|

Once

again, we can notice that much in a cartoon is close to the

philosophy of existentialism, which is saturated with the spirit of

absurdity. And many of the cartoons can be considered as the

illustrations of the statements of philosophers. But what about

surrealism, which in fact was born by the absurd? How close is

surrealism to the art of cartoons? A precursor of surrealism I.

Bosch already used the "oddities and quirks" with

paradoxical forms of mixing in his mysterious paintings. The same

methods were used by Salvador Dali, Paul Delvaux, Yves

Tanguy, Max Ernst, Rene Magritte...

The competition between surrealism and absurdity in the world

of cartoons was won by the last. Probably absurdity has a

relationship with the real world; it recognizes the laws of the real

world but denies these, thus creating its own laws. Surrealism does

not recognize any laws and exists by itself. |

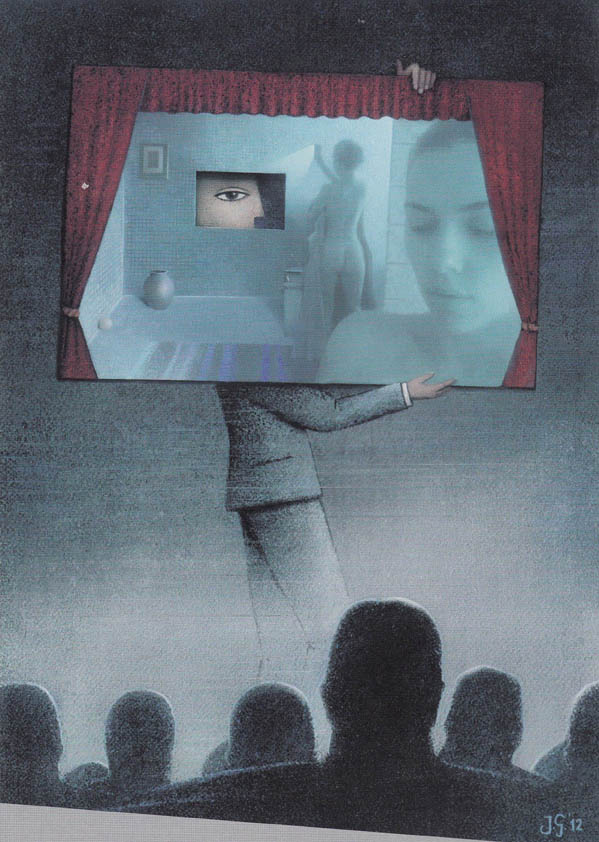

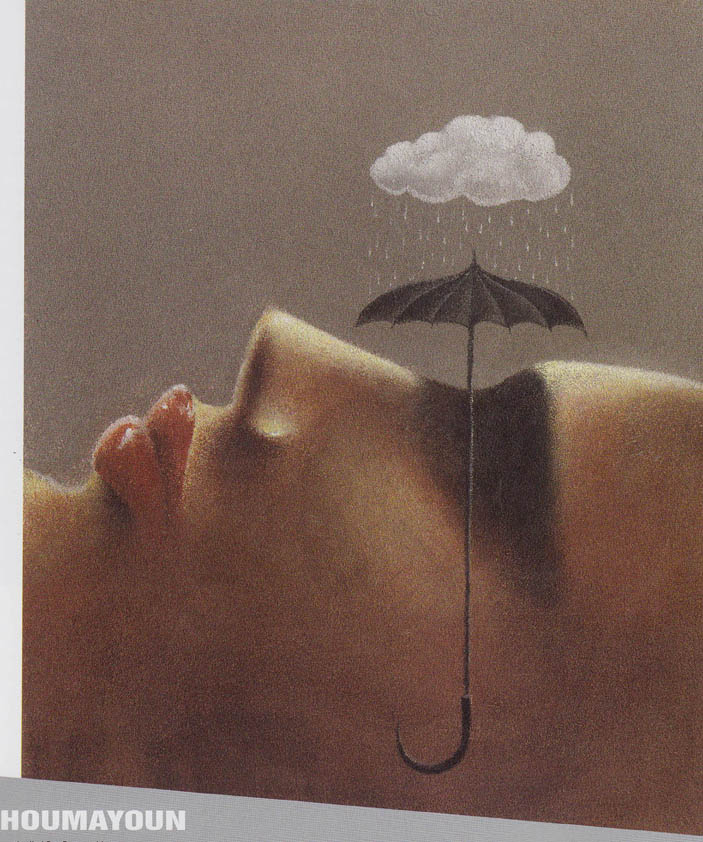

| However,

as we noted above, painting cartoons gradually began to conquer the

space of comics in the late twentieth century. It is in these works

that manifestations of surrealism can be seen. Such cartoons are not

constructed according to the laws of humor. Semantic contents of

these works are based on a mixing of concepts. This does not make

talking about these cartoons that they do not have "grotesque,

ironic, buffoonery". From this perspective, we can recall some

cartoons by artists such as Alessandro Gatto, Andrej Popov, Erzy

Glushek, Muhittin Koroglu, Florian Doru Crihana, Mahmoudi Houmayoun

and others. In the works of these masters of cartoons we can easily

discern echoes of surrealism (Fig. 10, 11). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It's

time to talk about the place of cartoons in society. Since the

existence of cartoon art humanity has plunged into the abyss of war,

has made scientific and technological leaps, has

detonated nuclear bombs, and has ventured out into cosmic

space and plunged headlong into Internet space... It can be expected

that in our day cartoon art has moved in the scale of human values. |

| Let's

go back to the time of occurrence and becoming a cartoon art.

Speaking about the pros and cons of humor, including cartoons, which

developed "in all areas, including politics, art, mass

communications, advertising, promotion of knowledge", Nina

Dmitrieva said, "Cons can be found in the exsanguination of

satire, which is dissolved and dispersed in a continuous stream of

humor and in lowering the value of the laughter as the strong

weapons hitting exactly the goal that is worthy of strike" [1,

261]. In other words, satire gave way to the absurd, with its own

specific sense of humor and irony. Cartoonists have started to show

an abstract collective man and a generalized absurd world. There was

no the place for satire in this world. The mural by artist Saul

Steinberg can be considered the apotheosis of the triumph of the

cartoons. It shows an ironic panorama of American society at the

World Exhibition in Brussels in 1958. Saul Steinberg was very

popular at the time in the world.

Around a hundred solo exhibitions of the artist

were organized in New York, Washington, Chicago, Rome, Milan,

Paris, Zurich, Hamburg, Vienna, Amsterdam and other cities. This

great cartoonist was not only the author of graphic works, but also

frescoes, opera scenes, posters [22]. |

| The

art of cartoons starts to win hearts of people in the second half of

the twentieth century. The cartoons confidently settled in Central

and Western Europe in the late forties - early fifties. From there

this kind of art migrated to Eastern Europe and began to conquer the

Soviet Union in the early sixties. The "wave" of cartoons

has swept Turkey and later Iran, after the revolution. As a result

of the easing of censorship and the actual opening of the borders, a

"cartoon explosion" occurred in China. Cartoons appeared

in Japan and South Korea, of course, influenced by American artists.

So, "the cartoon tsunami" swept across the globe from the

West to the East for half a century, excluding Japan and South Korea,

where it arrived across the Pacific Ocean from the East. This

striking march of the cartoon art suggests that humanity needs an

extraordinary ironic view of the world. And cartoons fully meet

these expectations. |

|

Notable

events in the world of cartoons are international competitions and

festivals, that emerged in the sixties of the last century. The most

popular, for example, are CARTOONFESTIVAL in the Belgian resort town

of Knokke - Heist, SATYRYCON in the Polish town of Legnica, DICACO

(2013 - SICACO) in the Korean city of Daejeon, INTERNATIONAL HUMOR

EXHIBITION in the Brazilian town of Piracicaba, PORTO CARTOON WORLD

FESTIVAL in the city of Porto and a lot of others. These cartoon

contests have their internal laws, codes, customs, habits and heroes.

In over half a century, they have been in touch with a whole

generation of artists. |

| One

of the oldest and most famous cartoon contests is organized by the

team of Japanese newspaper The

Yomiuri Shimbun. It existed

29 years and was closed in 2008. A total of 289554 cartoons were

sent to this competition.

The organizers had declared the official reason for the closure of

the competition was that the "contest has already made quite a

significant contribution to the art of cartoons." Around this

time, the interest to the art of cartoon in Japan began to fade

noticeably, says Ayako Saito, press drawing teacher of Kyoto

Seika University. |

| A

whole galaxy of new cartoons competitions have been organized in

recent years that mainly exist in virtual space. These competitions

have served as a good stimulus for the development of cartoon art. |

| Of

special note is one

phenomenon. As noted by many researchers, cartoon art originated in

New York city and later in Paris in the thirties of the last century.

But which kind of cartoons are popular in these cities today? It's

amazing, but, although cartoons are very popular in the world,

namely in France and the US, this art has lost its position. In

recent decades, in these countries the public has not been

interested in political cartoons or in traditional humorous drawings,

which have verbal support. Why? Cartoon art is popular in Turkey,

Iran, China, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, countries of the former

Soviet Union and in Eastern Europe countries... That is, in those

countries where there exist acute socio-political and economic

problems and there are many people who dissent with the social

injustice. Recall that cartoon art originated and developed in the

US and in France during the global economic crisis of 1929 - 1939.

This means that cartoons thrive in a social environment where the

dissatisfaction of the majority creates the need to release the

energy of social discontent. From this point of view, the art of

cartoon can be called "art of dissenters". |

| Totalitarian

regimes and tyranny are fertile breeding ground for the creation of

cartoons. For example, cartoons

penetrated the Soviet Union from across the relatively liberal

countries of Eastern Europe, in spite of the "iron curtain".

It should be recalled that the method of socialist realism

dominated in those days in Soviet

art. Official cartoons had to praise the party leaders and had to

criticize the external and internal enemies of socialism. Just such

official cartoons were published in the communist party press

without exception, and the only press was party press. But the

shoots of free thought appeared in the Soviet Union in the early

sixties of the last century, during the Khrushchev "thaw".

"Informal" cartoons began to be published in the newspaper

Literaturnaya Gazeta,

magazines Smena, Tourist

and other publications in these years. The art of cartoons became

very popular among the "dissent" intelligentsia.

Party functionaries called these "informal"

cartoons "the humor of young" [23]. In addition to the

novelty of the paradoxical nature and philosophical ideas of

cartoons, the intellectuals liked the allegory of this kind of art.

Published cartoons allegorically criticized the existing socialist

system. When in the seventies of last century Brezhnev regime

tightened censorship, it was too late. Nonconformist artist Sergej

Tunin described the works of cartoonists as "fuck off in the

pocket". "The allegory is universal because it is similar

to a mathematical formula, if it is accurate and elegant, it is

applicable anywhere, anytime. Any value can be substituted into the

"formula" to enjoy the wit of the artist as their own",

he noted [24]. |

|

Cartoon

art became firmly entrenched in Soviet society. Cartoonists -

nonconformists began to send their works to international

competitions illegally. The artists Valentin Rozantsev, Sergej Tunin,

Mikhail Zlatkovsky, Garif Basyrov, Leonid Tishkov and others were

honored with awards at many international festivals of cartoons.

Cartoonists began to organize underground exhibitions of cartoons,

and grouped together in informal amateur clubs [25]. Censorship

eased with the coming to power of Mikhail Gorbachev and cartoons

migrated to the pages of Mass Media. |

|

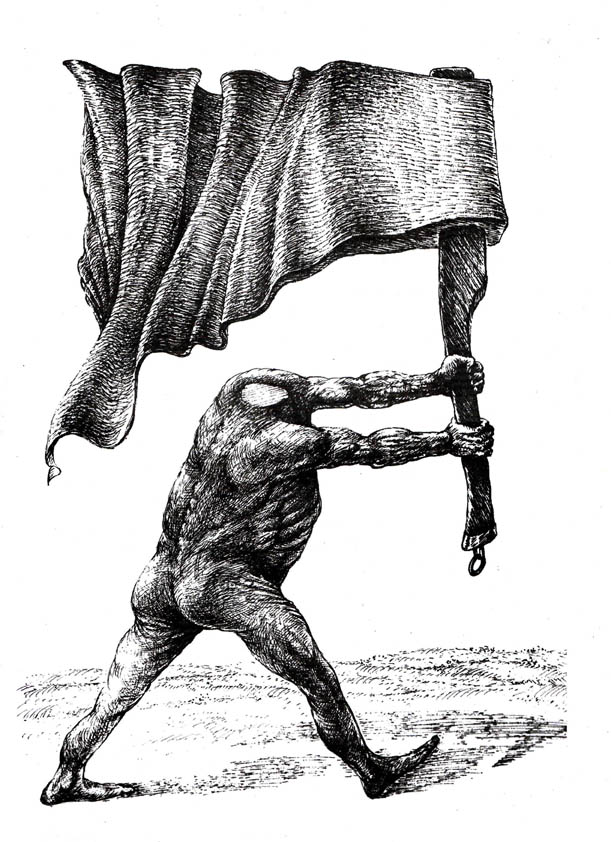

"There

are times when satire has to restore that which was destroyed by

pathos", so noted Stanisław Jerzy Lec. After the fall of

the "pathos" regime of the Communist Party, cartoonists

began to worry about new symbols and images in the former Soviet

Union. For example, one of the main characters of cartoons became

the flag. Obviously, because the flag was "untouchable"

for artists in Soviet times. A strong symbol of power turned into a

dirty doormat in the cartoons. Ruthless cartoonists allowed their

heroes to cut off the pieces of flag cloth to sew to sew on pants

and other clothing, or allowed them to clean their shoes with this

fabric... A headless man carries a flag that resembles an ax, that

was apparently used to cut off his head. This is one of the most

famous cartoon with the hero-flag construction, made by artist

Mikhail Zlatkovsky. For cartoonists the flag has become a convenient

tool for the expression of their social ideas (Fig.12). |

|

|

|

Another

object of ridicule used

by cartoonists in the countries of the former Soviet Union was the

ballot box, the ephemeral symbol of totalitarian power. The

political elections in Soviet times were formal acts where results

were a foregone conclusion. The people of the former Soviet Union

began to think about the elections quite differently . Political

elections became real, although often accompanied by fraud. The

ballot box has taken a worthy place in cartoons. Restless

cartoonists began to draw keyholes on ballot boxes, made them as

into hats of magicians, etc. |

|

Thus,

the irony in the art of cartoons in countries of the former Soviet

Union began to get a satirical coloring. |

|

Continuing

the conversation about the role of cartoons in today's society, we

must recall religion. How do believers relate to the art of cartoons

and, conversely, what do the ironic artists think about religion?

There were times in history when church leaders have hated

satirical drawings, but sometimes they asked artists to help in the

fight against religious opponents (for example, the struggle between

Catholics and Huguenots in France became a kind of "duel"

between satirical artists in the time of the Reformation).

It has happened that the secular authorities officially called for

the satirical artists to criticize religion (for example, in an

atheistic state of the USSR). On the contrary, the authority forbade

artists to create cartoons of religious subjects in some cases.

Korean professor Cheong San Lim called his dissertation "Christian

education utilizing cartoon and animation". This project

is based on the fact that in the Bible is widely used

containing elements that are inherent in cartoon art, i.e.

parable, symbol, dream, vision, satire, humor and allegory"

[26]. Professor tried to build a bridge between the art of cartoons

and religion by the using cartoons in a Christian education. |

|

In

the thirties of the last century formally religious cartoons emerged.

These were not anticlerical drawings. In such cartoons Bible stories

have helped the artists to convey a "secular" message. For

example, in many cartoons Noah's Ark

has served as an allegory of the protection of the

environment from pollution . Or cartoonists adorn a scene of the

execution of Jesus Christ with consumer advertising. They do not

criticize religion, but the dominance of inappropriate advertising.

Cartoonists liked to

depict the Last Supper on the eve of Jesus' execution as well, often

parodying the famous fresco by Leonardo da Vinci... Many other

characters of Bible became the heroes of cartoons by artists from

around the world. Jean Effel has created a series of comical

parodies of biblical scenes. |

|

Cartoonists

have not only exploited Christian religious imagery. Hindu god Shiva

who embodies the masculine universe frequently has appeared in

cartoons as well. One of the seven gods of happiness, communication,

joy and prosperity, Hotei, who was nicknamed "Canvas Bag",

was not only one of the characters of netsuke in Japan and China. `Cartoonists

like to depict this funny fat man. |

| The

cartoons that depicted the Prophet Mohammed were published in the

Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten

in September 2005. These publications have denoted the cross-cultural

conflict between the Muslim Arab world and the Western cultural

tradition. The confrontation escalated even more after the tragedy

in the office of the French satirical magazine Charlier

Hebdo in January 2015. We leave aside the essence of this

conflict, its ethical and social aspects. We are interested here how

this influenced the art of cartoons. We distinguish here only the

fact that the international community has given special attention to

the art of cartoons in the aftermath of these events. Many people

who have never been lovers and connoisseurs of this genre turned

their eyes tо cartoons. The role of cartoon art

has become more visible in society. |

| Thus,

cartoon art has become more popular in the world. Did this affect

the art of cartoons? Did cartoons changed under the influence of

social expectations? Recall that in the recent years the main

characters of cartoons have been terrorist and refugees, who are the

victims of terror and war criminals. A huge set of drawings on

similar themes was created by the cartoonists in the last

years. Such cartoons can be attributed more to satire than to humor.

Cartoons have become increasingly filled with sarcasm and irony. For

example, the sad photos of Syrian refugee boy thrown out on the

beach in the Turkish town of Bodrum have appeared in the global Mass

Media on the 2nd of September 2015. Cartoonists from all

over the world responded

briskly. Several hundreds of cartoons based on this photo were

published on the Internet and in print media within a few days.

Although the photo was so convincing that it did not require

interpretation. This once again tells us that the emphasis of

cartoons has shifted towards satire. "Exsanguenations of

satire" in the cartoons and its "dissolving and dispersing

in a continuous stream of humor" in the time of occurrence and

development of the cartoons, about which Nina Dmitrieva wrote, seems

to have stopped. There has even been a reverse process. |

|

So,

cartoons "without captions" have fascinated mankind for

almost a century. Responding to the expectations of the people who

have been disagreed with social injustice, it originated during the

Great Depression under the influence of innovative ideas in the

visual arts, literature, theater, philosophy. The hitherto fertile

breeding ground for cartoons serves not only social disadvantages,

but also progress. Some popular cartoon characters and plots became

obsolete with time, and new ones appeared. In recent decades there

were noticeable changes in visual representation of cartoons, as

well as in their semantic contents. Cartoons began to be filled by

colors, became more persuasive in terms of realism. Increasingly,

there are picturesque cartoons, in some of which are visible

manifestations of surrealism. However, cartoons remains to gravitate

toward the spirit of the absurd. And finally, the cartoons have

become increasingly filled by sarcasm and satire. The art of

cartoons is still ironic, a witty manifestation of

a rebellious spirit. |

|

References |

|

1.

Dmitriev, N.

1973 Humor paradoxes, magazine "Foreign Literature", №6,

Moscow. |

| 2.

Freud Z. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious,

1997 University Book, AST, St. Petersburg. |

| 3.

Tsigulevsky V.

1989 symbol, parody and paradox in the non-classical philosophy,

Shtiitsa, Chisinau. |

|

4.

Dictionary of World

Literary Terms: Criticism, Forms, Techniques,

1979

Boston,

Writer. |

5.

Stokes, C.

2015 The New

Yorker`s Ninetieth: Cartoons from 1925 to 1935, Internet:

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/new-yorker-ninetieth-

cartoons-1925-1935

|

|

6.

Hewinson, W.

1951

A useful selection of cartoons from the first 25 years,

arranged in chronological

units in The New Yorker Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Album,

1925-1950. New York, Harpet & Brother. |

|

7.

Sabo, J. 1994

Topor, Witty

World International Cartoon Magazine, №17,33-37. |

|

8.

Koestler, A.

1964

The Act of Creation, London, Hutchinson. |

|

9.

Coulson, C.

2003

Why is it so funny?: conceptual integration in humorous

examples, |

|

Internet

http://www.cogsci.ucsd.edu/~coulson/funstuff/funny.html9. |

|

10.

Fauconnier G. and Turner M.

1998

Conceptual Integration Networks, Cognitive Science 22,

133-187. |

|

11.

Hofstadter D. and Gabora L.

Synopsis of the workshop

on humor and cognition, Humor:

International 1989

Journal

of Humor Research, 2-4,

417-440. |

|

12.

Owen D.H.

An Affordance Theory

Analysis of Cartoon Humor, At Last The Last,

1988 WHIMSY

8, 134-139. |

|

13.

Suls J. M. A

Two-Stage Model for the Appreciation of Jokes and Cartoons: An

Information-Processing Analysis,

The Psychology of Humor,

Theoretical

Perspectives and Empirical Issues, Edited

by: Jeffrey H Goldstein,

81-100.

1972 Internet:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780122889509 |

| 14.

Камю, А.

1999 Бунтующий

человек,

ТЕРРА

Книжный

клуб,

Москва, 37. |

| 15.

Камю А.

Миф

о Сизифе.

Эссе об

абсурде,

Издательство

политической

1990

литературы,

Москва. |

|

16.

Шопенгауэр

А.

1900

Полное

собрание

сочинений

в 4 т. Т 1,

Москва,189. |

|

17.

Heidegger

M.

1950

Sein

und Zeit, Tübingen, 126 |

|

18.

Ницше Ф.

По

ту сторону

добра и зла,

Сочинения

в 2 т., Т. 2, Мысль,

Москва,

1900

361-362. |

|

19.

Ле

Бон Г.

Психология

народов и

масс,

Академический

проект, 238.

2011 |

|

20.

McDugall W.

1920

The group mind, Cambridge. |

|

21.

Trotter W.

1916

Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War,

London. |

|

22.

Динов

Т.

1986

Говорящее

молчание,

A PROPOS, c/o Jusautor, Sofia. |

|

23.

Ефимов

Б.

1976

Школьникам

о

карикатуре

и

карикатуристах,

Просвещение,

Москва. |

|

24.

Тюнин С.

2003

Золотая

фига в

кармане,

Афористика

и

карикатура,

ЭКСМО, |

|

25.

Златковский

М.

2002

Юмор

молодых.

Российский

институт

культурологии

МК РФ,

Москва. |

|

26.

Lim C. S.2003

Christian Education Utilizing cartoon and Animation,An

Applied

Research Project, Oral

Roberts University,39. |

| Cartoons Mentioned |

| Fig.1

М.

Zlatkovsky. "No captions",

Шутки

в

сторону!

Или

время

улыбнуться

всерьез,

Прогресс,

Moscow,

p.

8, 1990. |

| Fig.

2 Ares. "No captions", Internet: click

here- tıklayın |

| Fig.3.

P.

Kuczynski. "No captions", Internet: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=187772041640200&set=a.100573893693349.1073741828.100012222150502&type=3&theater,

2016. |

| Fig.4.

R. Topor. "No captions", International Cartoon Magazine

Witty World, № 17, 35, 1994 |

|

Fig.

5. B.B. Ghaith. "No

captions", Internet: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10154399324991810&set=a.10151227318136810.516054.594766809&type=3&theater,

2016. |

| Fig.

6. C. Gomez. GRAFICA. ARTE/INTERNACIONAL, Ano25/61, Brasil,

2007-2008 |

| Fig.

7. A.Sulaj. "No captions", Catalogue of 1.International

Bursa Cartoon Biennial, p. 39. 2007. |

| Fig.

8. P. Klucik. "No

captions", International Cartoon Magazine, Witty World, №

19, p. 37, 1995. |

| Fig.

9. J.-J. Sempe. "No

captions", Sauve Qui Peut, Denoel, p. 91, 1968. |

| Fig.

10. J. Gluszek, "No captions", Catalogue of International

exhibition Satyrycon, Legnica, p.85, 2012. |

| Fig.

11. M. Houmayoun, Catalogue of International exhibition Satyrycon,

Legnica, p.43, 2012. |

| Fig.

12. M.

Zlatkovsky.

"No

captions",

Михаил

Златковский,

Галерея

мастеров

карикатуры,

Выпуск №5,

Гликон

Плюс, Санкт-Петербург,

p.

9, 2009. |

|